Canada

ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE

VOL. 50, No.3, 1988

ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE

VOL. 50, No.3, 1988

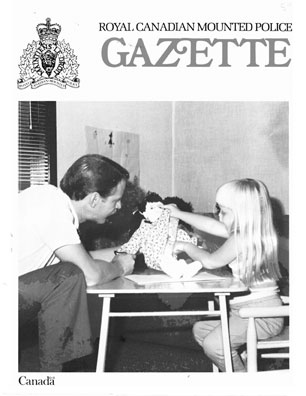

CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

by Cpl. Hunter McDonald,

Victoria RCMP Sub/Division G.I.S.,

Victoria, B. C.

Victoria RCMP Sub/Division G.I.S.,

Victoria, B. C.

PAGE 1 PAGE 2 PAGE 3

Interview Rooms And Equipment (Video)

If the offence occurred in the family home, do not conduct the interview there. Furthermore, it is vital not to interview the child seated on a couch or bed if the incident happened on or in any such location. A very young child may think because you are leading up to the problem, that you are, also, going to abuse him/her.

Each agency has different conditions in which to work. With some imagination and networking, it may be possible to create and share a child-oriented room. Mental health, public health and counselling services, all have facilities that may be suitable. During your networking, arrangements can be made on an as-needed basis.

This room should be "homey" with lots of pictures and drawings on the walls. Colouring and drawing supplies, along with toys should be available. Smaller children like to talk into toy phones and these can be acquired and wired into your recording system. Anatomically correct dolls and drawings, along with hand puppets, may be useful.

If possible, the room should be away from a busy police station.

Any agency in the enviable position of having input into the design of a new facility should request a special room equipped with one-way glass, unobtrusively placed video and audio equipment, and located in a low-traffic part of the building. These facilities can be shared by many agencies in order to justify costs. Recording equipment, if not available, can be rented for a nominal fee.

The ideal approach is to video-record the entire interview. Problems occur when children are non-verbal or talk too quietly. Video assists in objectively recording the nuances of body language communication as well as the child's own words.

The use of video in police work is a contentious and double-edged sword but, with controls and training, is a powerful instrument. A disclosure can be recorded and opinions sought from mental health personnel, prosecutors, police supervisors, or social workers who view it. Sometimes it can be shown to the supportive parent, in order that the primary and secondary victims may discuss the interview and issues raised during it.

During the interrogation of the offender, key portions of the tape can be shown in order to gain an admission. If a confession is obtained, the tape may be shown to the court during a Voir Dire. The tape may also be used in court during the sentencing of the offender. It is imperative that permission be obtained from the child and parent/guardian prior to any third party viewing the tape.

[ TOP ]

PREPARATION FOR DISCLOSURE FOR LONG TERM SEXUAL ABUSE

To gain the trust of a child takes time and effort. Without trust we will not be successful in obtaining an accurate disclosure.

Home Visits

Once a complaint has been received, it is vital that the police officer and social worker meet and discuss the process. One way to do this and save time is to meet at the child's home. It is best to meet the non-offending parent at the residence prior to the child coming home from school. Ensure that the child knows you will be there when she* arrives home. [*For the purpose of this section, we will assume that the victim is female. ]

The time spent prior to meeting the child assists the investigator to:

- assess hidden family agendas (Le., suppressed anger, impending divorce);

- view the scene (if applicable);

- support the parent(s) with material and advice;

- get photographs from family albums of all persons with the opportunity to have committed the offense(s). These can be used in the disclosure process;

- chart a chronology of the child's life (Le., list of schools, major events in her life and the ages at which they took place); and

- discover possible indicators (Appendix "A").

When the victim arrives home, you should put all your efforts into building trust and allaying her fears. For example, show her a picture of your interview room. Tell her about your contacts with other children, for example, "that you spoke to a little girl last week because she had a problem and that you are helping her with it. Maybe you can help her [the new victim] if she has one". If she is really young, you can tell her that you and your co-interviewer are "safety people". Tell her what is going to happen and answer any of her questions. The child can show you her room and pick a doll or toy she may wish to bring to the interview.

The benefits of meeting a child in her own environment are many, but include the following:

- she feels safe at home;

- you can assess her developmental level;

- you can assess which professional (in a two-person team) she relates to better;

- you can assess if the child is ready to talk; and

- you can establish a trusting rapport.

Prior to leaving, you make an appointment for the interview and give the child your card. The time you have spent is invaluable and will result in a less stressful interview for all concerned, coupled with a better knowledge of your fellow worker. Do not discuss "the problem" during this meeting, unless the child surfaces the issues.

[ TOP ]

Indicators

There are many signs that are evident when children are troubled and range from bedwetting to suicide (see Appendix "A"). The investigator must be aware of these when interviewing other witnesses, especially the parents. It is important to catalogue observations, especially dates of behavioural change. The absence of indicators does not mean that the charge is unfounded. The possibility of "hidden agendas" must be considered.

Young children are often the pawns in divorce cases and the accusation of abuse by one parent against another is not uncommon. The following observations could point to a false complaint:

- the child's sexual vocabulary is more advanced than normal, especially if it seems prompted and rehearsed;

- there is a lack of emotion about key issues;

- the child gives general details but not sensory details such as smell and touch, as would be expected;

- the story sounds rehearsed;

- the complaining parent insists on being present during the interview; and

- the child seems overly eager to please.

[ TOP ]

Cross-Cultural Factors

The fact that we deal with many indigenous and immigrant families, compounds the problems for the investigator as conducting an interview through an interpreter is difficult.

Many children are practising two cultures. At school, they are educated in North American attitudes and, at home, they may face the conflicting morals of their parents. Some adolescents caught in such a difficult situation may seek an escape. Hidden agendas for such adolescents must be borne in mind. However, the fact that they have complained against a parent, who represents their culture and their extended family, must weigh in favour of the teenager being believed.

It is vital that the investigator seek an understanding of the values, attitudes and systems that prevail in minority families. In most, if not all societies of the world, it is accepted that father and daughter incest is taboo.

[ TOP ]

Handicapped Victims

During your home visit, you may discover that the victim is either "developmentally slow" or emotionally or physically handicapped. Enlist the aid of a 5 specialist to assist you during the interview. Do not back off; patience and a thorough investigation may win the day by enabling a charge to be laid without the victim having to testify.

Cult-Related

If you suspect cult-related activities in an assault, extra sensitivity is required. Some disclosures are so bizarre that they may be dismissed as nightmares or over-active imagination, or even as signs of mental instability. Don't dismiss them so easily as there is sometimes some factual basis.

Credibility is a difficult issue for all persons, even psychiatrists, involved in dealing with victims of the occult. The book Michelle Remembers by Victoria, B.C., psychiatrist, Dr. Larry Pazder, illustrates the bizarre nature of disclosures involving the occult. In a recent Hamilton, Ontario, conviction, the judge referred to the occult in his decision thereby judicially recognizing the phenomena.

In some cases, the victim is told that if he or she confides the secret to someone, that individual will die as will the victim. References to flames, water, insects, blood, phases of the moon or human sacrifices in a disclosure must not be immediately dismissed. The damage to a victim's mental state must be considered. The assistance of a reputable professional, knowledgeable in the occult, should be sought prior to proceeding further.

[ TOP ]

Developmental Considerations In Interviewing

Children normally progress toward adulthood in fairly predictable stages, mastering skills at one level before moving on to the next. No two children develop at the same rate. Two children of the same age may vary greatly in physical, intellectual, or social maturity. But, a general knowledge of what children are like at certain ages is necessary if an interviewer is to choose the appropriate methods of gaining information and in assessing the child's responses.

The following descriptions are not intended to be all inclusive but rather 6 to stimulate discussion and further study. The descriptions focus on characteristics which are particularly relevant to the interview process.

[ TOP ]

The Pre-School Child

- develops language as the primary mode of communications between the ages two and four.

- does not understand abstract concepts; therefore verbal skills may imply more comprehension than actually exists.

- does not understand metaphors, analogies, irony.

- memorizes without comprehension.

- narrative accounts tend to be rambling and disjointed, with no distinction between relevant and irrelevant details.

- does not understand cause and effect.

- only focuses on one thought at a time; cannot combine thoughts into an integrated whole.

- memories are spotty and lacking in continuity and organization.

- concepts of time, space, and distance are not logical.

- is emotionally spontaneous with few internalized limits.

- can distinguish fact from fantasy.

- is capable of lying to try to get out of a problem situation, but believes adults have complete authority and would perceive any lie.

- is totally dependant on family for all physical and emotional needs.

- has egocentric perception of the world.

[ TOP ]

The School-Age Child

- begins gradual shift from total reliance on family to involvement with peers.

- identifies different roles for him/ herself

- student, child, peer.

- develops group loyalty, usually with members of his/her own sex.

- capable of practicing deception with adults as parts of establishing his/her own separateness.

- seldom lies about major issues, particularly in relation to justice and equality. Very sensitive to unfairness.

- develops increasing mastery of language.

- understands symbols but most thinking still concrete rather than abstract.

- knows who he/she is in time and space; understands concept of "others"

- intensely interested in understanding how things work.

[ TOP ]

The Adolescent

-undergoes profound physical and emotional changes as his/her body matures. relates to peer group, may have minimal rapport with adults, at least outwardly. needs to establish own identity separate from family.

- may question values and beliefs he/she has been taught.

-capable of deception and manipulation.

- outward show of bravado or hostility often covers feelings of shyness and inferiority.

- can think abstractly; understands metaphors, analogies, irony.

[ TOP ]

THE INTERVIEW

This takes patience with a child and cannot be rushed. She has to TRUST you on her own level - get down on the floor, take your jacket off, draw pictures, learn about her likes and dislikes, focus on happy things and talk about yourself as she needs to know you as a PERSON not just as a police officer.

Children are more communicative when they are busy colouring or playing. However, discourage them from moving around too much as it breaks the focus of the conversation and causes problems with audio and video.

Use this time to ask background questions to assist in gauging developmental level. Ask her if she knows why she is there. Explain the rules.

1) we only talk about what actually happened;

2) it is OK to say, "I don't want to talk anymore";

3) it is OK to say, "I don't know";

4) it is OK to say, "I don't remember"; and 5) it is OK to cry or ask for support.

[ TOP ]

THE PROBLEM

The use of analogies is a help in getting to the issue. The other children you, have helped can be of use in encouraging and focusing, without being leading. For example, "Yesterday I spoke to a boy who had a problem with his babysitter. Michael told us about the secret and the babysitter doesn't bother him anymore. Do you have a problem like that?"

This is a good time to talk about body parts. The use of anatomical drawings which allow the child to write or point to the various parts is useful in keeping him or her busy. They may become evidence, as do any drawings done by the victim. Bathing suit zones and private areas are useful topics in getting to the issue. Once the child's terminology has been determined, those are the words that should be used.

If the child appears "stressed", it may be beneficial to talk of happier things for a few minutes. If, part-way through the interview, you realize that she is not ready to talk, do not press, but continue on building trust. Ensure that the child knows you would like to talk to her in a week or so. Arrange for follow-up counselling if required.

It is now time to show the photographs supplied by the supportive parent. The use of family photographs assists in:

1. establishing the identity of a suspect(s);

2. eliminating any potential suspect and/or denies the suspect an easy way out, (a biological parent accusing a step-parent Le., "It must have been the new Daddy");

3. identifying any other unknown suspect; and

4. assisting in evoking reaction from the child.

Arrange the photographs with happy ones at the beginning and very happy ones at the end. When the child sees the suspect's picture, she may re-live the experience and disconnect from you. It is essential that the victim's trust be maintained at least until after the disclosure. Her favorite people should be the last topic during this process.

The same questions must be asked of the child when she is shown each person in each picture. For example:

INT: What picture is this?

VIC. It is #4.

INT: Who is in the picture?

VIC: Uncle Fred.

INT: Has Uncle Fred ever touched you in a way that made you feel sad or mixed-up?

VIC: No.

INT: Did you ever have to touch Uncle Fred in a way that made you feel sad or mixed-up?

VIC: Yes.

If the child says yes, whichever way you worded the question, do not stop and pursue that avenue. Show her the balance of the photographs as there may have been other offenders. Also, you may weaken the evidentiary value of the identification if the process is not completed.

At the end of the photo viewing, ask her if there was any other person not in the photographs who touched her. Support her by stating that you know how difficult this is for her.

If she is ready, it is now time to get the details through focused, but not leading, questions. It is imperative that open-ended questions be asked. Repeat the answer to her; use effective listening techniques to ensure she knows you understand what she has stated and to allow her to correct you if a point is cloudy. For example, "Are you saying then that Bob kissed you, is that what you said?" Speak up when repeating in case the recording equipment cannot pick up her voice.

If difficulty is encountered, several techniques are helpful. Have one interviewer take over or ask if one of the investigating team should leave. Suggest to the child that she think of the incident as it would be on a TV screen and VCR. This is a special screen as it can use slow motion, freeze, reverse or fast forward. This allows her to talk in the third person and to be an observer rather than a victim. With young children, you can use puppets, or anatomical dolls. Again, care must be used with the doll in order that defence counsel cannot discredit the disclosure process. This is a good chance to have the child draw diagrams of the scene (Le., suspect's residence and describe sights, sounds, smells and tastes).

[ TOP ]

The author, a native of Scotland, emigrated to Canada

in 1965 and

joined the St. Boniface, Manitoba, Police Department the following

year.

The author, a native of Scotland, emigrated to Canada

in 1965 and

joined the St. Boniface, Manitoba, Police Department the following

year. He joined the RCMP in 1969 and has worked general duty detachments, a highway patrol unit and marine services. He also participated in the E. R. T. programs, was a team leader for several years and has been a shift NCO and a detachment commander.

Cpl. McDonald lectures in the areas of cross-cultural education as well as child sexual assault and has done so for both the RCMP and the Justice Institute of B.C.

You may contact the author at:

inquiries [AT] childsexabuse.ca